To the sea, and beyond

Squint at the images released from the James Webb Space Telescope this summer—a black sky electrified by starry sparks—and you could be looking into another frontier, much closer to home: the deep ocean, alight with bioluminescent creatures and vastly underexplored.

Both frontiers—the earthly and the galactic—bring us a sense of wonder as we come progressively closer to understanding the nature and history of all life. To gaze into either space or the ocean is to look into the past. In space, we see light that left its source long ago. In the deep sea, we can see creatures that have walked—or swam, or crawled or simply sat on—the Earth for hundreds of millions of years. And, just like the dedicated space researchers behind Webb, all of us at Schmidt Ocean Institute are committed to boldly exploring the ocean, alongside the world’s marine science community.

But today, we know less about the deep sea than we do about the moon—even though we made it to the deep sea first. Nine years before Neil Armstrong’s giant leap for mankind, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh took a giant dive to 9,144 meters below, their submarine nearly buckling under the intense pressure found at those depths.

More than 60 years later, most of the ocean below 2,000 meters has not yet been explored. The landscapes first viewed by Piccard and Walsh are the least known places on our planet. Less than one-fourth of the seafloor has been mapped to high resolution. Such maps provide the basis for research and future discoveries, shed light on geological processes and may identify potentially valuable ecosystems.

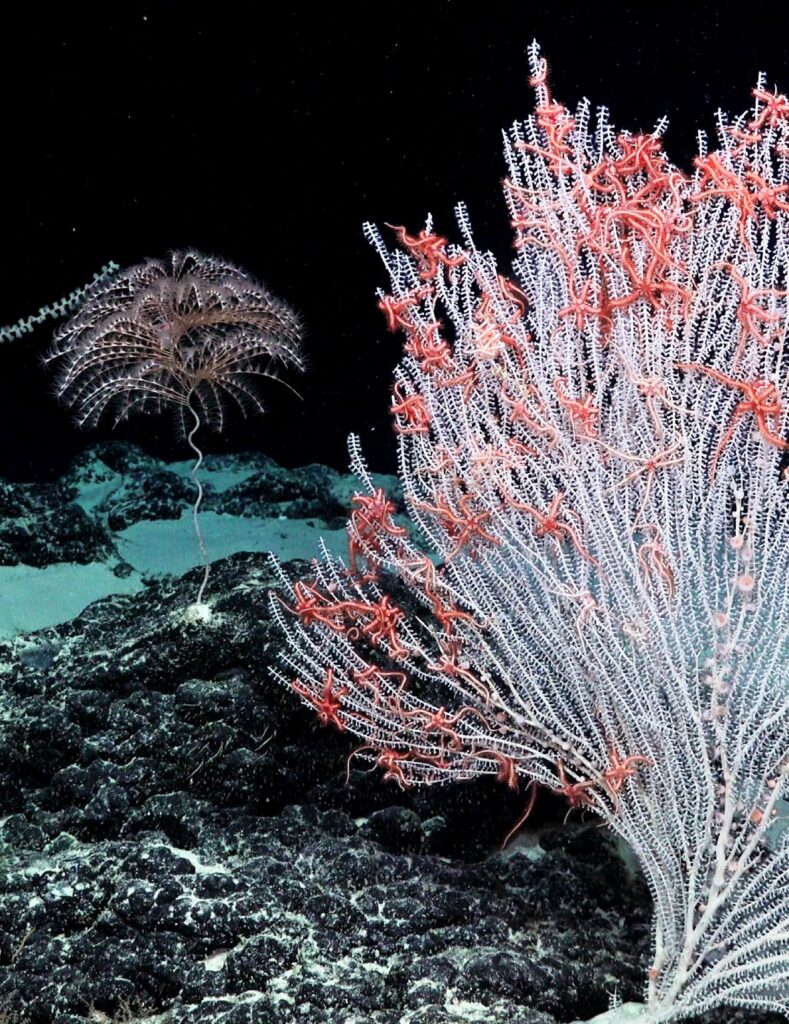

The creatures in the deep, too, remain little known. Much of that marine biodiversity, particularly in the deep sea and at microbial levels, is unknown, even though ocean compounds have been used to develop medicine for AIDS, cancer and recently for COVID-19. Understanding life on this planet can also give us an insight into potential forms of life on other planets—the hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the sea could provide clues about similar vents on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

The human population is intimately tied to the ocean in ways we are only beginning to understand. We need to do a better job explaining that connection and how human activities impact it. We cannot afford to lose any more species, habitats or ecosystems that may hold the answers to carbon mitigation, potential new diseases, or how to save creatures threatened by warming temperatures.

My hope is that our exploration and investment in the ocean will stimulate public interest and lead to increased support for the new technologies that enhance our understanding and protection of the ocean habitats we already know, and the ones yet to be discovered.

To explore is to better understand the ocean systems that matter to us all. We are in a revolutionary time for ocean science: we are able to work together in ways that are far more efficient, forward-thinking and inclusive. This fall, Schmidt Ocean Institute will set sail on its new research vessel, Falkor (too), capable of traveling to further reaches across the world’s ocean and conducting more science missions with its modular design. Falkor (too) is our commitment to working towards a more collaborative global understanding of our ocean systems. With more than 35 berths for scientists and other participants, Falkor’s ability to conduct more science, outreach and data analysis is expanding and will allow for broader and more diverse participation on board. As we take our maiden voyage, and head into the third year of the Ocean Decade, we hope you’ll join us in bringing all the wonders of the sea to light.

Wendy Schmidt is co-founder with her husband Eric of Schmidt Ocean Institute. The couple also founded Schmidt Futures and the Schmidt Family Foundation, which Wendy leads as president.